As his co-worker prepared to speak at our Building Forward: Sustainable Growth Forum Joel Kotkin was researching and writing The Battle for Houston. Read the article below.

Originally Posted: August 15, 2018 on city-journal.org

Over the last half-century, Houston has developed an alternative model of urbanism. As the New Urbanist punditry mounts an assault on both suburban growth and single-family homes, Houston has embraced a light regulatory approach that reflects market forces more than ideology. But last year’s Hurricane Harvey floods severely tested the Houston model. An unprecedented four feet of rain in four days—a year’s worth, the greatest rainfall event in recorded U.S. history—overflowed the banks of every channel in Harris County, flooded nearly 100,000 homes (7 percent of the housing stock), and created an estimated $81.5 billion in damage, the nation’s second-largest natural disaster after Hurricane Katrina. Coupled with a downturn in the energy industry, which saw the loss of some 86,000 jobs last year, Harvey’s aftermath suggested that the region’s growth period had come to an end, with stagnant job growth and domestic migration.

A year later, the city’s economy and its energy industry are rebounding, and job growth has gone positive again. Houston is once again among the nation’s leaders in population and housing growth. The recent recovery, however, is unlikely to quash the growing pressure to revise the region’s growth model. Challenges to Houston’s approach can be found everywhere from writers for theHouston Chronicle to the urbanists at Rice University—both representing an increasingly powerful clerisy capable of challenging the long-running dominance of the local commercial and real estate interests that have always promoted growth and expansion as signs of virtue. Houston’s business community tends to ignore or dismiss the critics, but experience elsewhere should encourage caution. In California, once dominated by growth-happy free marketers, business interests have been largely neutered by environmental zealots, government unions, and social-justice militants. And a shift in national priorities, with a Democratic takeover of Congress and the White House, would greatly enhance the power of the “smart-growth” lobby to impose its vision, even in Houston.

Houston is famous for its lack of zoning, which has allowed for speedy transition of the housing stock, including a surge of high-density housing close to the city’s historic core. But as a new paper from the local Center for Opportunity Urbanism suggests, most of the region’s growth occurs on the periphery. In 1960, the City of Houston dominated the region; today, Houston is home to barely one out of three of the area’s roughly 6.8 million residents, with almost all growth on the pro-development edges.

Houston has long had in place deed restrictions to maintain the integrity of residential neighborhoods as well as significant development guidelines for commercial projects. Yet the generally light regulatory hand has resulted in a remarkable level of affordability, even with strong job and population growth. Among the 15 largest metropolitan areas, Houston ranks first in housing affordability (tied with Detroit), while cities like San Francisco, Los Angeles, and New York are among the costliest, adjusted for incomes. Houston is also fifth in rental affordability (median gross rent divided by median household income) among major U.S. regions, at 19.6 percent, below the national average of 20.4 percent.

Since 2010, the Houston area has trailed only Dallas–Fort Worth among major regions in rate of net migration, while New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago have all suffered massive net out-migration. Houston has won by giving people what they want, including an affordable single-family home; low costs are critical to understanding the city’s appeal. Admittedly, people don’t move to Houston for topography, climate, or historical charm. As author Erika Grieder notes, no one moves to Houston “for fun,” but for opportunity. “Everyone who is there,” she writes, “is there for a practical reason.”

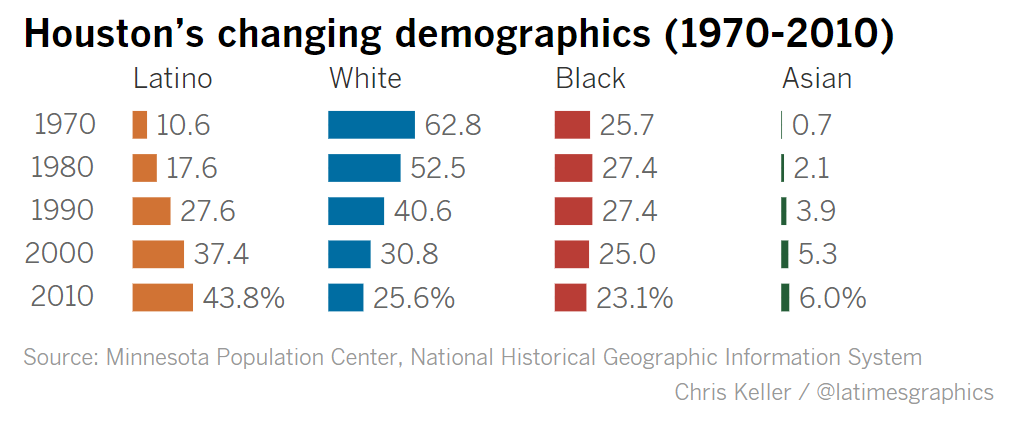

Perhaps most impressively, Houston excels at accommodating minority aspirations. The region is now widely acknowledged as the country’s most diverse. Houston offers the most affordable U.S. rents for African-Americans, with rent absorbing 25.4 percent of income, considerably less than in highly regulated markets like San Francisco (45.3 percent), Miami (37.2 percent), and Los Angeles (37 percent). Among Hispanics, Houston’s rental affordability ranks fifth among the top 15 metropolitan areas.

Like other immigrant hubs, Houston suffers from high income inequality, but Houston’s minority middle class has been expanding at a rate unmatched by blue-state metropolises. Among the largest metro regions, Houston ranks first in housing ownership—a critical signal of upward social mobility—for African-Americans, and second for Asians; it’s tied for the lead for Latinos with Atlanta and Dallas–Fort Worth. Houston’s level of overall minority homeownership is ten percent higher than in such bastions of progressivity as Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York, or Boston.

This low-cost structure—largely the result of policy—has been key to sparking job growth. Businesses generally find recruiting easier in Houston, given the range of housing options, and residents have enjoyed one of the country’s highest cost-adjusted standards of living, ranking well ahead of rivals such as San Francisco, New York, Los Angeles, Seattle, and Chicago. These gains have been bolstered by an increasingly varied economy that produces a high percentage of mid-wage jobs in fields such as energy, trade, and medical services. In the past decade, Houston has not only consolidated its domination of the energy industry but also become the nation’s leading exporter and home to the world’s largest medical center.

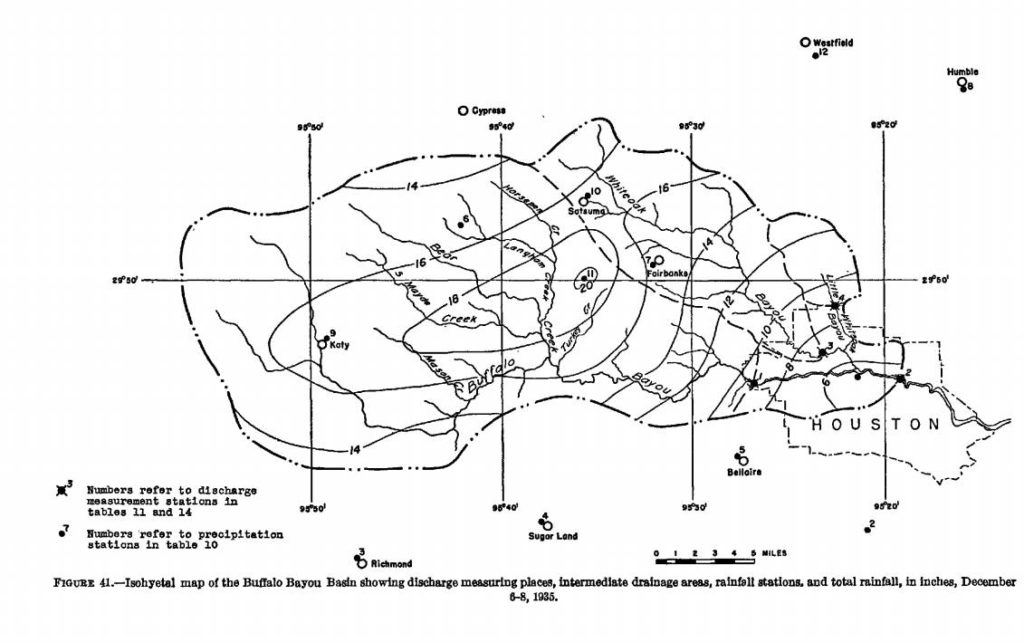

Houston is largely an engineered city. Its success does not owe to a perfect location, a salubrious climate, or spectacular scenery. Situated far from a natural harbor, this bayou city was forged, in large part, by the 1914 decision to build a ship channel that connects it with the Gulf of Mexico, 50 miles away. Its location makes Houston susceptible to natural disasters. Long before Harvey, Houston was devastated by hurricanes, including the one that destroyed the once-thriving port city of Galveston in 1900. A 1935 flood caused more severe damage, proportionally, than Harvey did, on a then much-smaller Houston.

Historically, Houston has met these challenges by seeking to tame nature. A relevant model can be found in the Netherlands, where, for hundreds of years, planners managed to push back against the sea, in the process creating one of the world’s great metropolises (Amsterdam). Historian Jonathan Israel traces the rise of the Netherlands, particularly following a massive flood in the sixteenth century, to its period of extensive infrastructure-building. Like Houston’s suburban expansion, infrastructure development in Holland opened new land and opportunities for residents. It also initiated liberal laws about tenancy and allowed for the expansion of ownership and enterprise, much as Houston’s expansion accomplished over the past half-century. The new lands constituted “the geographic roots of republican liberty,” notes historian Simon Schama.

Like the Netherlands, Houston built an elaborate, if now inadequate, system of flood-control channels and dams. The city’s business community still follows this infrastructure-led model, as evidenced by Harris County Judge Ed Emmett’s 15-point resiliency plan and the business-backed “Houston Stronger” plan for $58 billion in infrastructure projects for water conveyance, storage, and surge defense. To help pay for it all, Harris County will hold a $2.5 billion bond election on August 25. Though it will increase property taxes by up to 1.4 percent, the taxpayer value is substantial, since the funds can be leveraged 4-to-1 or more as the local match for federal funds.

In the past, such an investment would go unchallenged, but public skepticism about new infrastructure is growing, along with demands for stricter regulation, particularly toward development on the fringes. The Harvey disaster gave momentum to both these trends. Days after the storm hit, Ana Campoy and David Yanofsky of digital news outlet Quartz opined: “Houston’s flooding shows what happens when you ignore science and let developers run rampant.” Further afield, Guardian climate columnist George Monbiot portrayed the event as a kind of karmic comeuppance for Houston’s being the world capital of the planet-destroying energy industry. New York Times architecture critic Michael Kimmelman essentially suggested that Houston should emulate dense and transit-dominated Manhattan.

Houston’s small but influential urban intelligentsia has embraced these views. Mike Snyder of the Houston Chronicle, for example, blamed municipal-utility districts and suburban developers for the severity of the flooding. Similarly, the Rice Design Alliance called for the creation of a “thick” (meaning denser) city, with an enhanced role for traditional transit. This suggestion is at odds with recent experience, however: despite opening 22 miles of light rail since 2004, for example, Harris County transit ridership has dropped, while the county’s population has grown by nearly 1 million.

A big win for the “smart-growth” crowd has been a new regulation adopted within the City of Houston, which mandates raising houses off the ground—but these new rules, suggests economist Luis Bernardo Torres, a real estate expert from Texas A&M, will disproportionately hurt poorer, older, heavily minority areas. “I think we are passing the buck,” says Greg Travis, Houston District G City Council representative. “The city has been underfunding drainage improvements for decades, and now we want to make everyone elevate. City Hall needs to take responsibility for flooding instead of pushing it onto homeowners.” A 2018 Metrostudy report estimates that the new regulation could add an additional $65,000 to the costs of building or reconstructing a house in the city, compared with building in the surrounding or less regulated areas.

The battle within Houston boils down to emphasizing regulatory restraints, rather than infrastructure, as the best means to meet floods and hurricanes, which some expect to worsen with climate change. The smart-growth lobby generally sees raising elevations for houses and reigning in “sprawl” as the best solution to the city’s environmental challenges. Concern over suburbanization runs high: the Houston Chronicle opined that steps such as building a proposed third reservoir might be inadvisable, since it could enable new peripheral development. These views reflect the conviction that the severity of flooding was largely due to the paving over of the Katy prairie west of the city. Yet an analysis of the run-off by Meyers Research showed that the area’s natural soils, with their poor suitability for retention, would have absorbed only 4 billion gallons out of the 1.6 trillion gallons that fell on Harris County, a savings of a mere .25 percent. “Anyone suggesting that more wetlands or more pervious surfaces would have done anything to mitigate what has just happened is lacking a proper sense of scale,” says Charles Marohn of the media organization Strong Towns.

Houston’s newer suburban areas actually withstood the flood far better than older communities inside the city. According to Harris County’s engineering staff, of the 75,000 homes built after the 2009 regulations, only 467 flooded; a remarkable 99.4 percent did not. Less than 3 percent of the houses identified as flooded after Harvey were built after 2009. These newer homes complied with the drainage and detention regulations adopted after Hurricane Allison.

Looking forward, suburbs could be important players in addressing intense storms. Alan Berger, co-director of MIT’s Norman B. Leventhal Center for Advanced Urbanism, suggests that lower-density areas, as opposed to highly built-up cities, are ideal for detaining water. Celina Balderas Guzmán, a wetlands researcher and Ph.D. student at the University of California-Berkeley, argues that suburban areas could provide “a new paradigm for managing storm water” and that the best solutions “will be those that shift away from mono-functional, centralized infrastructure.”

Some of this can already be seen in the improved performance of detention ponds in Houston’s lower-density areas during Harvey. These initiatives can be expanded into “constructed wetlands” that mimic natural wetlands, using the same physical, biological, and chemical processes to treat water. Besides treating storm water pollution and detaining floodwaters, constructed wetlands can boost biodiversity and provide urban amenities such as recreation.

Houston already has many communities, such as the Woodlands, designed to absorb storm water through natural means. These developments suffered limited damage during Harvey—only about 0.2 percent of the population in the Woodlands needed to be evacuated. Better-planned suburbs could well be the “secret sauce” for addressing Houston’s challenges without destroying its growth-and-opportunity model.

Without question, Houston will need to update some regulations and boost its infrastructure if it wants to meet the challenge of future storms. The real question is whether flood control opens the gates for a smart-growth agenda that could seriously weaken Houston’s affordability and growth trajectory. This will depend largely on political factors. Though the region overall continues to follow a free-enterprise model, with Democrats and Republicans both embracing a low-regulation agenda, the City of Houston has become more smart-growth-oriented in recent decades. Business and political leaders shouldn’t underestimate the power of academic institutions, legacy media, and allied nonprofits to advance that cause. The battle has just begun, and the future of the Houston model hangs in the balance.